The late Stephen Hawking dedicated much of his life to the potential discovery of a unifying theory of everything, attempting to find consistency in the universal laws that define existence on both micro and macro levels. As an artist when much of your world is measured in millimeters and fractions thereof, a project spanning several feet can certainly feel like an entirely different dimension! A four-foot-tall sculpture would be considered small by some sculptors. However, after years of fastidiously crafting jewelry to tolerances sometimes within a few hundredths of a millimeter it certainly expanded the horizons of my creative processes.

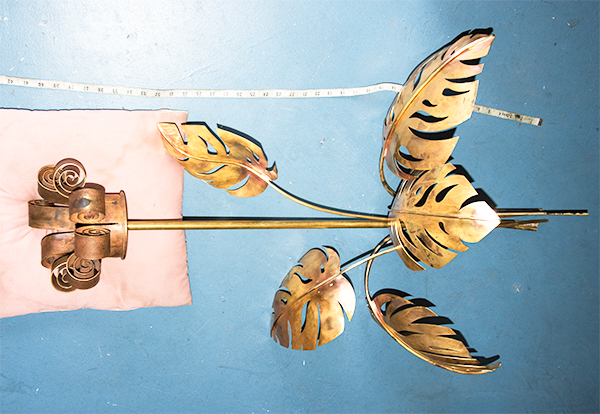

Although this is not the first large metal sculpture I have crafted it is by far the biggest and reached proportions that required additional changes to familiar processes. Over several years I have occasionally created floral sculptures out of spent brass artillery shells from WWI and WWII. Each piece has presented its own challenges as they have progressively grown in size.

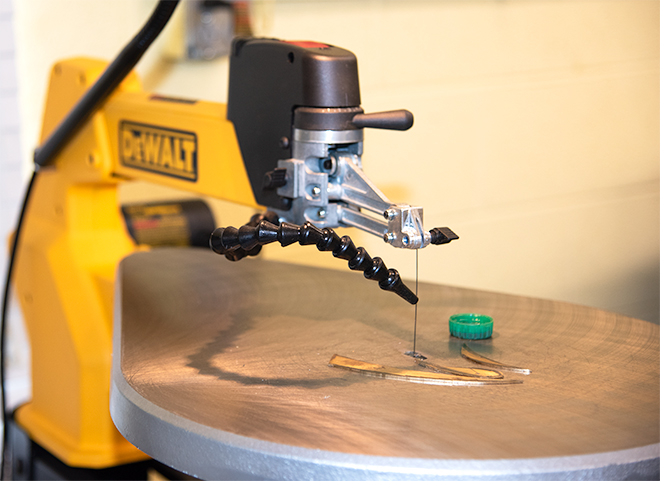

The leaves of this creation were inspired by tropical leafy philodendrons. In my array of air tools for larger projects I did not have anything that could handle the tight turns and open details of my envisioned greenery. A trip to Woodcraft Supply for a scroll saw soon followed; a favorite toy store for any craftsperson! The staff at their Roanoke location is just wonderful and full of valuable advice and even have a few floor models designated as demo units. Scroll saws are not normally used for large metal projects and I cannot endorse or recommend using them for such. However, I found that inserting a jewelers saw blade in place of a standard scroll saw blade worked well enough to achieve the arching contours I had conceptualized.

This rather ambitious 52” endeavor involved a 105mm artillery shell casing. The 105mm is used in the mobile artillery cannons known as Howitzers. This cartridge casing stood unloaded at about two feet tall. Once cut and curled into a blossom it was naturally a bit shorter, though still sizable. Together with substantial brass leaves, stems and other components the colossal metal flora required a considerable base. The river provided a lovely yet immensely heavy foundation in a large sandstone polished smooth by currents and time. Now moving such a wonderful find was another matter. Some basics in driving a Caterpillar first to move the stone and later driving a trailer to transport the finished piece soon followed.

One of the greatest challenges in the process was the assembly. An extraordinary amount of time in fabrication is dedicated to positioning components on a solder pad. For small metal projects this involves various magnesium or charcoal blocks, tweezers, third arms and anything and everything heat resistant that can be used to prop parts into a proper and secure position for brazing. Aligning large, heavy, meticulously formed shapes requires quite a bit of additional thought as some of my small “go to” props were now obsolete. On several occasions my mind explored the countless ways I could easily manage these parts if they were all just a few feet smaller.

Ultimately joining each large stemmed leaf to the stock was best executed with free access to the base that the flower would be set into when finished. This meant taking one of my torches, “the big torch”, to a friend’s property by the river and assembling it near the sandstone. I brought an army of magnesium blocks and every soldering pad in my arsenal of brazing supplies both in tact and in broken bits. These did not actually get me very far and I quickly resorted to stacking stones into careful piles to brace each part in preparation for brazing. Due to the nature of the design once I began affixing each component there was no turning back until all the brazing was complete. The last leaf was by far the most arduous to position. By this time the entire structure was perched atop a precarious pile of stones and fire bricks and previously arranged parts could not be disturbed. Even with two filler materials of different melting points, five attached parts in the same area can be challenging. A shift in the position of the design could have easily caused parts already connected with brazing wire to melt and fall off or result in a complete collapse if proper structural support was not present and completely independent of brazed connections.

Metalworking encompasses a tremendous variety of techniques and processes and very few if any master them all. Even when focusing solely on nonferrous metals there is always more to discover. This project was certainly enlightening and gradually blossomed into a truly unique art piece over the months I toiled away creating it.